In Conversation with Ugo Azuya: Diving into Dreamscapes, Swimming in a Sea of Trauma And The Fluid Art of Remembering

By Thelma Ideozu

- 3rd July 2024

Perhaps it is this lack of romanticism; the clarity of simply following one's intuition and seeing where it leads that allows Ugo to approach his craft with continuous curiosity and a level-headed optimism, even in the face of obstacles. “I’ve received many rejections along the way,” he says, in his frank, easygoing manner.

“But I knew that I would move forward if I was disciplined and willing to improve my work. It’s a continuous process, making films; just like growing up is a process. There’s a lot I still don’t know”.

We sat down with the young artist to explore the making of the film and the mind of its maker:

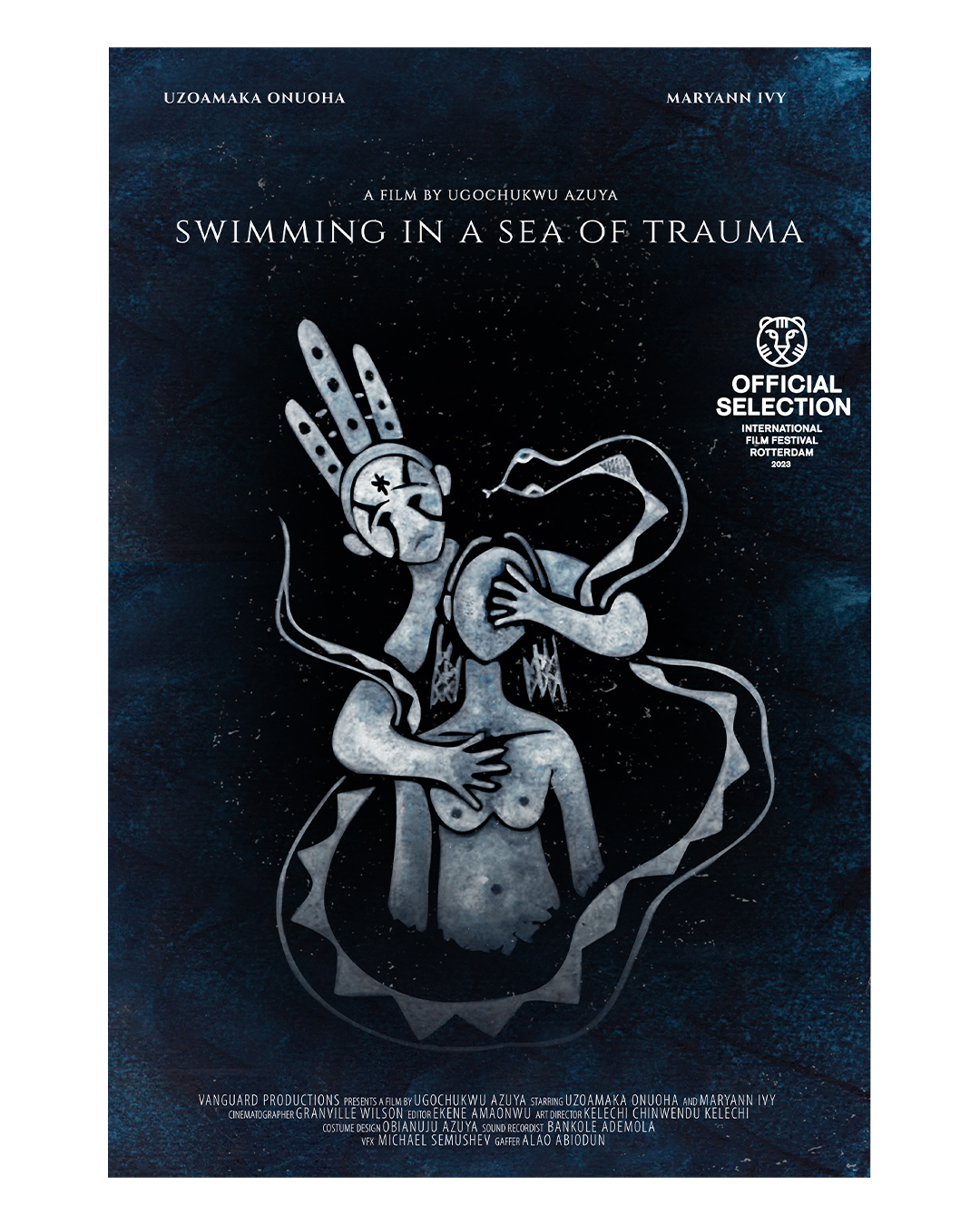

Ugo: That was due to the wonderful collaborators I had on the film. Editor and sound designer, Kene Amaonwu pitched the idea to me while we were working on the post production and i relayed the idea to Kelechi Chinwendu Kelechi, an Igbo artist who created the female ancestral mask, the film’s gorgeous poster illustration and that title card design. Her work is daring, intelligent and fearless. One of the highlights of making the film was the true sense of collaboration we had and I'm indebted to every single person who worked on the film with me. It was a joyful experience.

Q: The first animate being we meet in the story is a python. We later learn of another python, Eke, who we are told whispered into the ears of Nkechi in the forest. Since we know that the python is venerated as a messenger of water deities in certain Igbo communities, it begs the question: what were your intentions behind the use of Eke and any symbolism it may carry?

Ugo: I try to stay away from symbolism and focus on portraying reality.

Q: It’s immediately clear that the protagonist(s) in the film is plagued by a silent anguish. How did you endeavor to capture this cinematically?

Ugo: I think of the film as not only exploring a political memory but of a personal and ancestral memory. The fact that we can emphasize another person’s predicament speaks volumes.

Q: This is undoubtedly a stirring film. How do you want the viewer to feel during your film and afterwards?

Q: You’ve managed to touch on a number of crucial topics (including collective memory, shared trauma, and mental health) in under 7 minutes. What were some of the unique challenges or experiences you encountered during production?

Ugo: With any film there are always challenges at all stages. When the script was ready we had to wait an extra month for budgetary reasons, but it allowed me to use the time to my advantage and make some last minute revisions. I like to work on the script until the final day, if I can.

Q: Ultimately, what message(s) do you want your work to convey?

Q: What role do you think history plays in shaping the present and the future, particularly in the context of the Igbo people? What would you say are the dangers of succumbing to a culture of historical amnesia?

Ugo: William Faulkner once said that the past is not dead. I'm not sure I remember his exact words but I think he’s right. I think of the film as a ghost story about the memory of the Biafra War. When we speak of ghosts, I think we are more haunted by the memory of the relationship we had with that particular individual than the idea of an eerie figure. The past never really leaves us and life presents itself in strange and uncanny ways. I believe the world suffers from this historical amnesia that we speak of, and it creates certain psychological effects in us, collectively and as individuals.

It’s even worse in Nigeria where history isn’t really taught in schools. This is a deliberate amnesiac operation which leads to the distortion of historical facts.

Q: What advice would you give to young (Igbo) people trying to start out in the film industry?

Ugo: Our practice should be taken with a certain seriousness, discipline, fearlessness, integrity and desire to promote different ways of thinking and seeing the world. Filmmaking is a collective effort: a group of people working to bring the film to life. In the Mbari system [an Igbo visual art form], the master artist worked with other artists to build an Mbari house for the sake of community. I think this is a good way of thinking about filmmaking.

Q: What’s next for Ugo? What else can we expect from you?

Ugo: My next short is a science fiction film about the climate crisis. I’d also like to explore more themes and nuanced aspects of Igbo culture in my work, and possibly even shoot some book adaptations along the line. But my dream is to produce a full-length feature film in the future.

‘Swimming In a Sea of Trauma’ has enjoyed resounding success on the film festival circuit, having been screened at Lago Film Festival (Italy); Lobo Film Festival (Brazil); Johannesburg Film Festival (South Africa); Light Matter Film Festival (USA); Alliance Francais Open Cinema Screenings (Nigeria) and Wetin Dey: an evening of eclectic short films from Nigeria (United Kingdom). While speaking on people's reactions to the film, Ugo describes an interaction with an older woman who approached him after a screening to tell him how the story had moved her spirit . “You don't always realize how much your work might affect people, " he reflects. “But this also makes you aware of the responsibility you have as an artist to tell authentic stories.”