Road to Omenuko: The Role of Western Religion in the Development of Written Igbo Language and Literature

Literature is as ancient as communication itself. From the earliest gatherings around a fire, where people exchanged tales and songs from generations past, literature has been a vital part of human culture. Similarly, the Igbo language is as old as the Igbo people, with precolonial Igbo literature primarily transmitted orally.

Over time, written communication among Ndi Igbo has evolved from the ancient Nsibidi script, which was used in regions adjacent to the Cross River, to the standardized form used today. This transition from oral tradition to written expression owes much to the influence of early missionary churches.

In 1857, Samuel Ajayi Crowther led a mission on behalf of the Sierra Leone-based Church Missionary Society (CMS) of the Anglican Communion, establishing the first church in Igbo land, located in Onitsha. As part of their efforts to ensure the success of their missions in Africa, missionaries were encouraged to study and learn indigenous languages for effective communication, with a particular focus on producing Bible translations and catechisms in these languages.

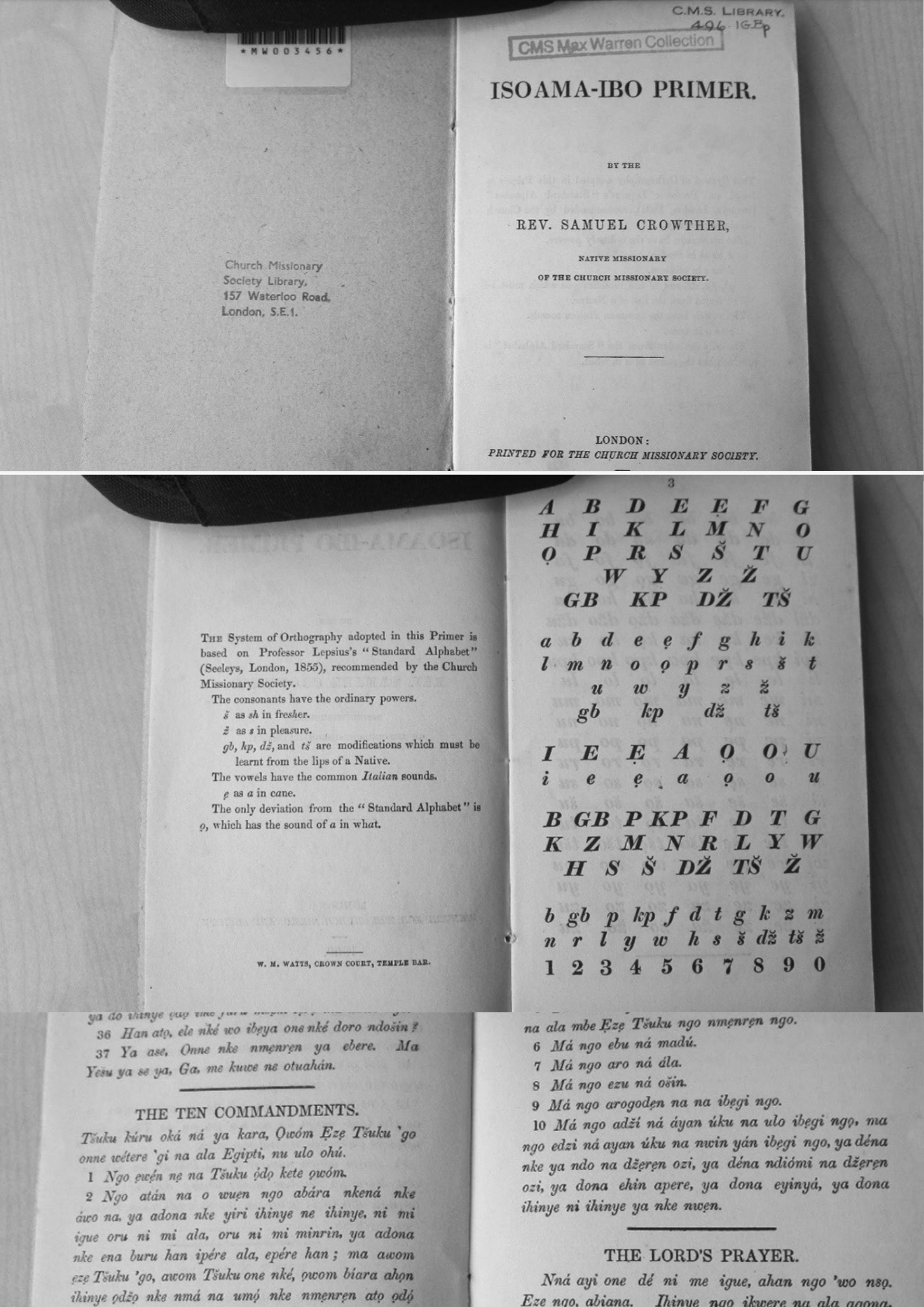

In line with the Niger mission, Rev. Crowther prepared and published ‘Isoama-Ibo Primer’ in 1857, marking the first significant literary work in the Igbo language. The Primer included translations of select chapters from the Gospel of St. Matthew, the Igbo alphabet, sentence patterns, vocabulary, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Ten Commandments. It was written in the Isuama dialect, which was prevalent among Igbo ex-slaves in Sierra Leone. However, the multidialectal nature of the Igbo language presented a significant challenge for missionaries in their linguistic studies.

Pages from Isoama-Ibo Primer

Pages from Isoama-Ibo Primer

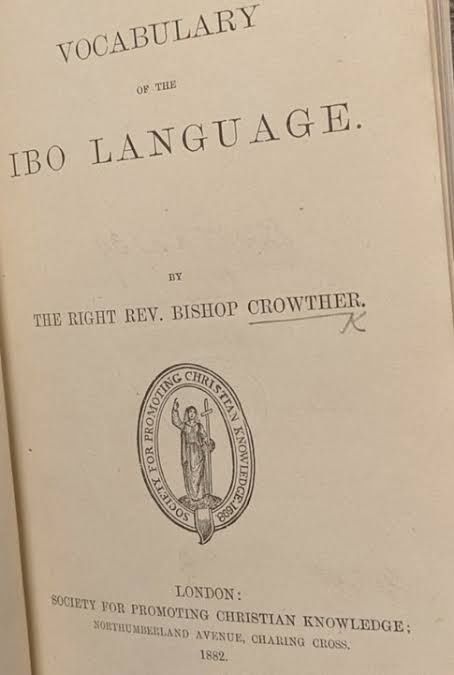

The Primer preceded the establishment of rudimentary schools, which were often conducted under trees or in makeshift school rooms. For decades, it served as the primary textbook for teaching reading and writing to the Igbo people. This linguistic studies continued with the publication of works such as ‘Grammatical Elements of the Igbo Language’ by Schon in 1861, ‘Vocabulary of the Igbo Language Parts I and II’ by Crowther in 1882 and 1883, and ‘A First Grammar of the Ibo Language’ by Spencer in 1901. Crowther’s original Primer eventually evolved into ‘Ibo Reader I and II’.

In addition to Crowther’s Primer, the Bible played a pivotal role in the development of written Igbo language and literature. After the passing of Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther, Archdeacon T. J. Dennis, a trained linguist, joined the Niger mission. He convened indigenes from diverse backgrounds to form the Igbo Language Translation Committee, which, in the early 20th century, undertook the task of translating portions of the Bible into Igbo. Egbu, near Owerri, was selected as the committee's headquarters due to Owerri's reputation as one of the places where the "purest form of Igbo” was spoken.

The translation project commenced in 1906, encompassing dialects from Onitsha, Owerri, Unwana, Arochukwu, and Bonny. The Union Igbo was one of the earliest attempts to standardize or centralize the Igbo language. Translation efforts concluded in 1912, and the Union Igbo Bible was published a year later. It was widely embraced as a unifying force to discourage further fragmentation within the Igbo community.

In addition to the Bible, Rev. Dennis and his committee translated other religious texts, including Pilgrim’s Progress, catechisms, the Union Reader, and the Union Hymnal, during what is known as the Union Igbo Studies Period (1900-1929).

Despite its widespread acceptance, the Union Igbo initiative sparked debates, particularly among members of the Anglican Church in Onitsha. Critics argued that Union Igbo was an artificial construct that threatened to erode the authentic forms of expression among the Igbo people. Additionally, other Christian denominations in Igbo land favored using local dialects over Union Igbo in their evangelistic endeavors.

However, the most significant debates in the development of written Igbo language centered around its orthography. In 1927, the International Institute of African Languages and Culture (IIALC) in London published the ‘Practical Orthography of African Languages’, which conflicted with the ‘Lepsius Orthography’ used by the Church Missionary Society (CMS) for Union Igbo. This disagreement ignited the "great orthography debate," with the colonial government and Catholics on one side and the Protestants on the other. The dispute between the ‘Roman Catholic Orthography’ and the ‘CMS Orthography’ dragged on until the 1960s.

In 1939, Dr. Ward conducted research, sponsored by the colonial government, leading to the development of what became known as central Igbo language, primarily based on the Owerri and Umuahia dialects. While the colonial government, Catholics, and Methodists embraced central Igbo, the Anglican Communion adhered to Union Igbo.

Eventually, in 1961, the Eastern Region government established an orthography committee led by Dr. Onwu, which brokered an accepted compromise. This compromise involved the use of diacritical marks to distinguish between heavy and light vowels. The government mandated the use of the ‘Onwu Orthography’ in Igbo studies, and its development continued for decades thereafter.

In addition to the translation and publishing of religious material, the mission also began to explore Igbo folktales, proverbs, riddles, and sayings, collecting them for publication. When the original Primer was revised and expanded in 1927, it included 19 secular essays, a narrative riddle about the sun, and 18 folktales, which served as educational materials.

It is worth noting that parents who sent their children to school at this time were not seeking an alternative or substitute education; they already had an efficient traditional educational system but hoped to supplement it. They also opposed teaching the children about the foreign religion in school, as they felt the children received sufficient religious teachings at home. Although the missionaries accepted these terms, they did not intend to adhere to them fully. The essays published in the revised Primer were somehow linked to the Bible. For example, in an essay on farming as a major occupation of the Igbo people, this was written: "When God created the first man, the occupation he bequeathed to him was farming, as we learn in the Bible." Similarly, the folktale about the Leopard and the Lamb aimed to "urge the poor to find strength in Christ’s promise that blessed are the poor for they shall inherit the earth."

With this strategy, the Christian religion was not only being taught to the children but was also being integrated into the fabric of our culture and beliefs. They were altering traditional Igbo narratives to align with Christian teachings. It is no surprise that even when Igbo writers took on the mantle of championing Igbo literature, most early works sought credibility and foundation in Christian teachings.

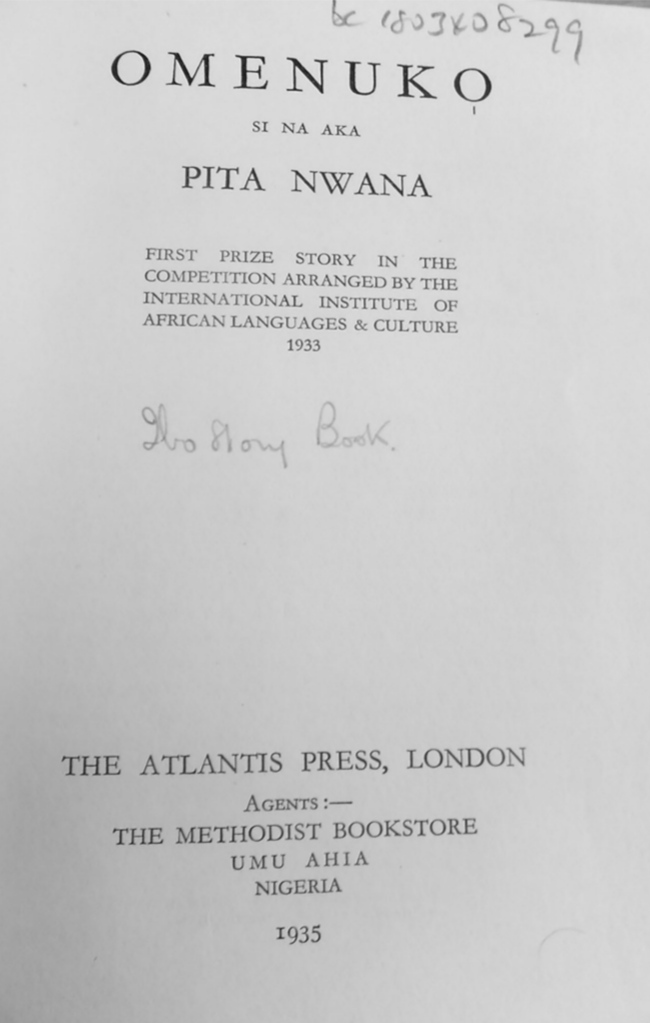

The history of written Igbo literature is incomplete without recognizing the first Igbo novelist and his work. In an effort to promote African indigenous languages, the IIALC organized contests for works written in African languages. Pita Nwana’s Omenuko, a biography tracing the life of its protagonist, Omenuko, on a lifelong journey, won the Africa-wide literary contest and was published in 1933, becoming the first-ever published Igbo novel. While its initial edition was in the ‘Protestant Orthography’, other orthographies were soon introduced to accommodate its wide acceptance and readership.

References

The Literary History of the Igbo Novel; African Literature in African Languages (2020). Ernest N. Emenyonu

L. C. Chinagorom & N. T. Onuorah, The Origin and Evolution of Igbo Language and Culture over the Generations (2018); Journal of Humanities vol. 1 no 1.

A. U. Igwe & N. Obiakor, The Historical Emergence of ‘Union Igbo Bible’ and its impact on Igbo Language Development in the Twentieth Century (2015); International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development 2(1): 70-75